University tuition fees rising to £9,535 in England

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUK students will pay more for university in England next year, as undergraduate tuition fees rise to £9,535 a year.

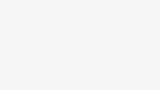

It is an increase of £285 on the fees, which have been frozen at a maximum of £9,250 since 2017.

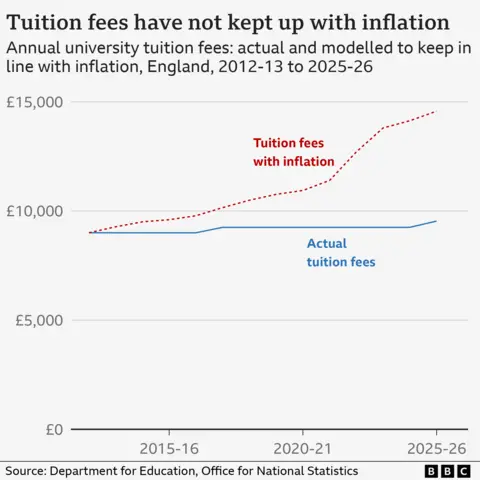

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson told MPs in Parliament on Monday that maintenance loans would also go up to help students manage the cost of living.

The National Union of Students called the tuition fees rise a “sticking plaster”, but said higher maintenance loans “will make a real difference to the poorest students”.

For universities, the higher fees are a cash injection to assist with their most immediate financial challenges.

However, the announcement only affects fees and loans in the 2025/26 academic year – and vice-chancellors will want to know what the government’s plans are beyond that.

Phillipson said the government would announce further “major reform” for long-term investment in universities in the coming months.

She said the government was having to “take the tough decisions needed to put universities on a firmer financial footing”.

But she told the BBC they would also be “demanding more of universities”, and looking at things like how much top bosses are paid, in order to “drive better value for students and for the taxpayer”.

Prime Minister Keir Starmer had said he wanted to abolish tuition fees altogether when he ran for the leadership of the Labour Party in 2020.

But in 2023, he said Labour was “likely to move on” from the pledge. In this year’s general election campaign, he confirmed he would be doing so as he wanted to prioritise spending on the NHS.

In the Commons on Monday, Conservative shadow education secretary Laura Trott called the tuition fee rise “a hike in the effective tax graduates have to pay”.

Next year both tuition fees and maintenance loans will be linked to a measure of inflation called RPIX, which counts the cost of everything except mortgage interest costs.

It is currently set at 3.1%.

That will increase maintenance loan caps from £10,227 to £10,544 for students living away from their parents outside of London, and from £13,348 to £13,762 in London.

Maintenance grants, which were non-repayable, were scrapped in 2016.

In their analysis of the changes, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) said the tuition fees increase would spare universities a further real-terms cut to their teaching resources.

But they urged the government to say whether fees would continue to increase after next year, “to provide some certainty to universities and prospective students alike”.

They also said that, under current repayment terms, around a quarter of the extended loans would eventually be written off and paid by the taxpayer.

Although students taking out the highest possible maintenance loans would be getting more money next year, the IFS said they would still be borrowing 9% less in real terms than they would have done in 2020/21.

The changes announced on Monday will affect students starting university next year, as well as current students – although universities can have contracts that protect their students from fee hikes part-way through a course.

Students Shay and Zay, both in their first year studying product design at Manchester Metropolitan University, said higher fees could put off prospective students.

Branwen Jeffreys / BBC

Branwen Jeffreys / BBCZay said tuition fees were “already quite a big factor playing on a lot of people’s minds” when deciding whether to go to university.

Shay said university was “already expensive as it is”, but added that he was more worried about his maintenance money being able to cover the cost of living.

Personal finance expert Martin Lewis has said the tuition fee changes are “likely to be trivial”, especially compared with students who started university in 2023.

Last year, loan terms were increased from 30 to 40 years and repayment threshold salaries were dropped from £27,295 to £25,000, meaning more graduates would be repaying their loans for longer.

Tom Allingham, from the Save the Student money advice website, said that despite their “dismay” at the increase in fees, it would make “little difference to overall levels of student debt, and will have no impact whatsoever on the amount a graduate repays each month”.

That sentiment was reflected by sixth formers in Oldham considering their university choices for next year.

Niamh, who wants to study English literature, said tuition fees were not rising by a “huge amount”, but that maintenance loan increases were “definitely needed” to support students.

She said costs for university students were “ridiculous”, so “even a little bit of extra support is welcome”.

James, who wants to study engineering, said he thought it was “unfair” that he was going to have to work to help fund his living costs at university, even with the increased maintenance loans.

Hope Rhodes / BBC

Hope Rhodes / BBCSarah Coles, head of personal finance at Hargreaves Lansdown, a financial services firm, said parents of young children should start saving now for their university years.

She advised parents of older children to “be clear about what level of financial support they can expect from you”.

Vivienne Stern, chief executive of Universities UK, which represents 141 universities, said the government’s decision to change tuition fees was “the right thing to do”.

She said the freeze had been “completely unsustainable for both students and universities”.

But Jo Grady, general secretary of the University and College Union, said raising tuition fees was “economically and morally wrong” and that the government was “taking more money from debt-ridden students” to support universities.

The changes come after growing concerns about the state of university finances in the UK.

The Office for Students, the higher education regulator in England, warned that 40% of universities have predicted a deficit in this academic year.

In July, Phillipson said universities should “manage their budgets” amid calls for the government to bail out struggling institutions.

Universities UK has previously suggested tuition fees would need to rise to £12,500 a year to adequately meet teaching costs.

But they also acknowledged that asking for that amount would seem “clueless” and “out of touch”.

The government hopes that increasing maintenance support will help students with day-to-day living costs like food and accommodation.

But higher tuition fees and increased maintenance loans will mean students need to borrow more to go to university, and will leave with more debt.

The Department for Education will publish an impact assessment soon, alongside legislation setting out the changes. It will look at the impact of the changes on students’ debt at graduation, and their repayments over time.

The tripling of fees in England in 2012 prompted widespread protests.

Since then, they have only increased once, in October 2017, when then-prime minister Theresa May announced a £250 rise.