Q2 Data Analytics Earnings: Palantir (NYSE:PLTR) Impresses

2024-10-02 12:36:48

Let’s dig into the relative performance of Palantir (NYSE:PLTR) and its peers as we unravel the now-completed Q2 data analytics earnings season.

Organizations generate a lot of data that is stored in silos, often in incompatible formats, making it slow and costly to extract actionable insights, which in turn drives demand for modern cloud-based data analysis platforms that can efficiently analyze the siloed data.

The 5 data analytics stocks we track reported a satisfactory Q2. As a group, revenues beat analysts’ consensus estimates by 2.6% while next quarter’s revenue guidance was in line.

Inflation progressed towards the Fed’s 2% goal recently, leading the Fed to reduce its policy rate by 50bps (half a percent or 0.5%) in September 2024. This is the first cut in four years. While CPI (inflation) readings have been supportive lately, employment measures have bordered on worrisome. The markets will be debating whether this rate cut’s timing (and more potential ones in 2024 and 2025) is ideal for supporting the economy or a bit too late for a macro that has already cooled too much.

Luckily, data analytics stocks have performed well with share prices up 23.3% on average since the latest earnings results.

Best Q2: Palantir (NYSE:PLTR)

Started by Peter Thiel after seeing US defence agencies struggle in the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks, Palantir (NYSE:PLTR) offers software as a service platform that helps government agencies and large enterprises use data to make better decisions.

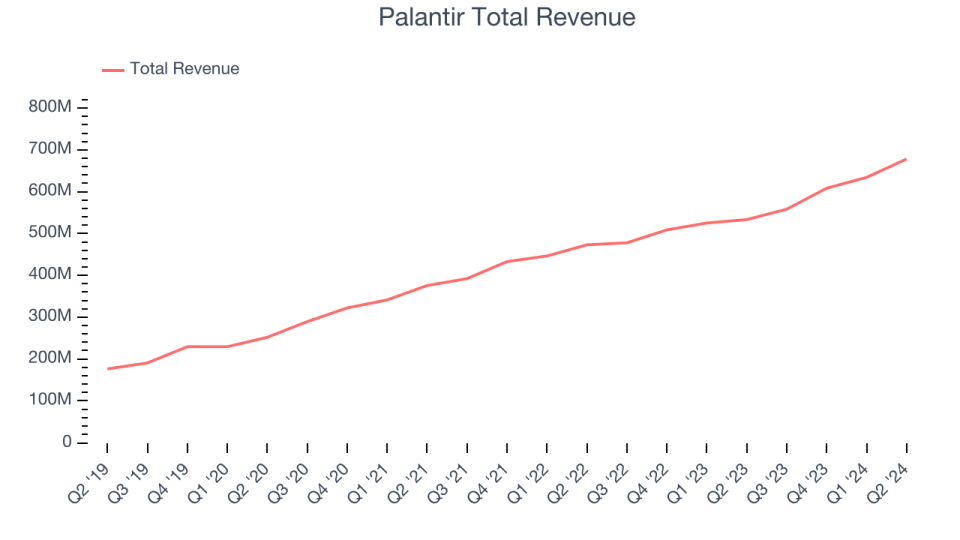

Palantir reported revenues of $678.1 million, up 27.2% year on year. This print exceeded analysts’ expectations by 3.9%. Overall, it was a very strong quarter for the company with an impressive beat of analysts’ billings estimates and optimistic revenue guidance for the next quarter.