US president Donald Trump arrives in Scotland for four-day visit

BBC Scotland News

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUS president Donald Trump said “it’s great to be in Scotland” as he landed for a four-day private visit.

After Air Force One touched down at Prestwick Airport, just before 20:30, the US president was met by Scottish Secretary Ian Murray and Warren Stephens, US Ambassador to the UK.

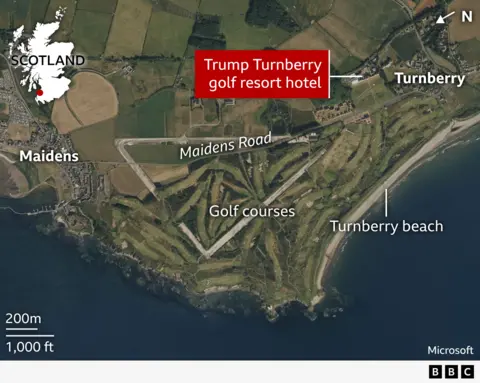

Trump spoke to journalists before the presidential motorcade left for his Turnberry resort, in South Ayrshire, where he is expected to play golf on Saturday.

Speaking about Sir Keir Starmer, who he is due to meet on Monday, he said: “I like your prime minister. He’s slightly more liberal than I am – as you probably heard – but he’s a good man. He got a trade deal done.”

Trump added: “You know, they’ve been working on this deal for 12 years, he got it done – that’s a good deal, it’s a good deal for the UK.”

The president earlier also described Scotland’s First Minister John Swinney as “a good man” and said he was looking forward to meeting him.

Swinney has pledged to “essentially speak out for Scotland”.

The motorcade – which contained more than two dozen vehicles – entered Trump’s Turnberry golf resort at about 21:30, flanked by Police Scotland vehicles and ambulance crews.

As he arrived at the luxury hotel, the president’s vehicle – known as The Beast – passed a small group of protesters.

Trump will stay at Turnberry over the weekend before heading to his second property in Aberdeenshire, where he will open a new 18-hole course at Menie.

He told reporters a late James Bond star played a crucial role in the project.

Trump said: “Sean Connery helped get me the permits – if it weren’t for Sean Connery we wouldn’t have those great courses.”

Trump is expected to meet Starmer and Swinney on Monday while European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen confirmed on X that she will meet the president on Sunday to discuss transatlantic trade relations.

Trump will travel back to the US on Tuesday and is due to return to the UK for an official state visit in September.

A number of protests are expected to be held to coincide with the visit, including demonstrations in Edinburgh and Aberdeen on Saturday.

A major security operation has been under way in South Ayrshire and Aberdeenshire this week, ahead of the president’s trip.

Dozens of officers have also been drafted in to support Police Scotland, under mutual aid arrangements, from other UK forces.

Road closures and diversions have been put in place in Turnberry, while a security checkpoint outside the resort and a large fence has been erected around the course.

A number of police vans have also been seen at the Menie site.

Getty Images

Getty Images PA Media

PA MediaSpeaking to journalists at Prestwick, Trump said European countries need to “get your act together” on migration, and “stop the windmills”, referring to wind farms.

He said: “I say two things to Europe: Stop the windmills. You’re ruining your countries. I really mean it, it’s so sad.

“You fly over and you see these windmills all over the place, ruining your beautiful fields and valleys and killing your birds, and if they’re stuck in the ocean, ruining your oceans.

“Stop the windmills, and also, I mean, there’s a couple of things I could say, but on immigration, you’d better get your act together or you’re not going to have Europe anymore.”

In 2019, his company Trump International lost a long-running court battle to stop a major wind power development being built in the North Sea off Aberdeen.

Trump argued that the project, which included 11 wind turbines, would spoil the view from his golf course at Menie.

Trump also claimed that illegal migration was an “invasion” which was “killing Europe”.

He said: “Last month, we (the United States) had nobody entering our country. Nobody. Shut it down. And we took out a lot of bad people that got there with (former US president Joe) Biden.

“Biden was a total stiff, and what he allowed to happen…. but you’re allowing it to happen to your countries, and you’ve got to stop this horrible invasion that’s happening to Europe; many countries in Europe.

“Some people, some leaders, have not let it happen, and they’re not getting the proper credit they should.

“I could name them to you right now, but I’m not going to embarrass the other ones.

“But stop: this immigration is killing Europe.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesQuizzed on the latest developments with the Epstein files and Ghislaine Maxwell’s interview with the Department of Justice, Trump said he had “really nothing to say about it”.

“A lot of people are asking me about pardons obviously – this is no time to be talking about pardons.”

He said the media was “making a very big thing out of something that’s not a big thing”.

Earlier, Chancellor Rachel Reeves told reporters the US president’s visit to Scotland was in the “national interest”.

Speaking during a visit to the Rolls-Royce factory, near Glasgow Airport, she said: “The work that our Prime Minister Keir Starmer has done in building that relationship with President Trump has meant that we were the first country in the world to secure a trade deal.”

Reeves added that it had a “tangible benefit” for people in Scotland, from the Scotch whisky industry to the defence sector.”

Swinney said his meeting with Trump would present an opportunity to “essentially speak out for Scotland” on issues such as trade and the increase of business from the United States in Scotland.

The first minister said he would also raise “significant international issues” including “the awfulness of the situation in Gaza”.

And he urged those set to protest against the president’s visit to do so “peacefully and to do so within the law”.

PA Media

PA Media PA Media

PA MediaVisits to Scotland by sitting US presidents are rare.

Queen Elizabeth hosted Dwight D Eisenhower at Balmoral in Aberdeenshire in 1957.

George W Bush travelled to Gleneagles in Perthshire for a G8 summit in 2005 and Joe Biden attended a climate conference in Glasgow in 2021.

The only other serving president to visit this century is Trump himself in 2018 when he was met by protesters including one flying a paraglider low over Turnberry, breaching the air exclusion zone around the resort.

He returned in 2023, two-and-a-half years after he was defeated by Biden.

PA Media

PA Media

Trump does have a genuine link to Scotland.

His Gaelic-speaking mother, Mary Anne MacLeod, was born in 1912 on the island of Lewis in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides and left during the Great Depression for New York where she married property developer Fred Trump.

Their son’s return to Scotland for four days this summer comes ahead of an official state visit from 17-19 September when the president and First Lady Melania Trump will be hosted by King Charles at Windsor Castle in Berkshire.